Digging Deeper Into Technology

What do you think of when you think of technology? Maybe you think of human-made devices that help us achieve a function: tools. You might imagine railroads, electricity, cars, airplanes, computers, the internet, mobile phones, and artificial intelligence. Maybe you conjured up a telescope or a hammer.

Or maybe you’re in the software industry like me and other things come to mind. For us, technology is our software applications and libraries, AI models and pipelines, compute and data infrastructure. It’s our open terminals, code editors, and collaboration tools. It is the business applications and internal workflows that our IT teams manage. It may be our company’s secret sauce, product, or the overall experience someone gets when they visit our website or download our software.

Could there be any value for someone in technology startups to dig deeper than that into technology? The tech industry is about doing and doing it fast. I learned that quickly by being an engineer, founder, and mentor in the Silicon Valley tech startup ecosystem. We quantify everything we can and value all that is useful, efficient, and actionable. Find what it is that you need to do and then do it. Slow is fake. See an opportunity? Take it. Popular articles & newsletters like the First Round Review or Farnam Street contain estimated reading times, frameworks, mental models, templates, actionable takeaways, and executive summaries. Often we take on this modus operandi simply because we need it to survive in the playing field. Fair enough.

In an industry driven by speed and quantifiable outcomes, the idea of diving deeper into something that appears self-evident seems counterproductive unless we knew it could help our efforts.

But in the industry we also like to take risks and think heretically. Might we find fresh, better modes of thinking and doing if we question what we already know? Might we improve the way we build businesses and technology products if we spent more time thinking about the meaning and implications of what we are building, in addition to how to make it and how to make it most efficiently? I think we might. To do so may be both liberating and immediately useful. Let’s dig deeper into the definition of technology to investigate the possibility.

A Deeper Look: Heidegger’s Technology

If technology is human-made stuff around us that helps us achieve goals, then are public institutions like governments or religious organizations technologies? That’s not how we typically use the word. So maybe we could require that technology refers to concrete artifacts. But would we call a computer program a concrete artifact? Were it small enough and if I were dedicated, I could keep it in my head. In that case, we have to admit technology could refer to know-how as well. That’s not surprising. Technology is often understood as know-how or applied science.

Maybe we can get clear if we consider our most ubiquitous technological objects. Technology was required to create my phone. But I also understand my phone itself as technology. The things “in” it are also technology. My web browser, calculator app, or TikTok are ‘tech.’ But what about Minecraft, Roblox, or Among Us? I would call those games, or maybe digital experiences, even though they appear to live within something we have always called ‘technology’. Even just a few more moments of reflection and technology becomes difficult to locate.

To investigate a complex concept effectively we can deploy philosophical techniques. We could continue to question our way into a deeper perspective ourselves. Instead, let’s turn to the work of others who have already done that. If we consult the influential philosophical literature it does not take long to find Martin Heidegger’s1 view on the essence of technology.

In his highly influential essay “The Question Concerning Technology” from 1954, Heidegger presents what he calls the ‘essence’ of technology. That essence isn’t something technological; it has nothing to do with the artifacts and techniques we commonly associate with the word ‘technology’. Instead, the essence of technology has to do with how the world appears to us. In that sense, we can understand it as a subjective phenomenon.

We can usefully interpret Heidegger with a metaphor: technology operates like lenses that change how we fundamentally see (i.e. understand) the world. There are different possible lenses or ways in which the world could be revealed. Technology is one of them.

Under the lenses of technology the world becomes a collection of resources to be extracted, ordered, on-call, and put to work with maximum efficiency. With the lenses of technology a river becomes a source for hydroelectric energy. A tree becomes lumber.

Heidegger uses the word “Bestand,” translated as “standing-reserve,” to refer to this essentially technological understanding of objects in the world.

Heidegger’s Technology in the Technology Industry

If you’re in the technology industry maybe you have already thought of several examples of Heideggerian technology in the world. Here are a few that come to my mind.

Concepts in Data Engineering Technologies. In the context of technologies that move and process large quantities of data such as Airflow or Dagster, we commonly refer to the data itself as an asset or a resource. These terms are not neutral regarding the essential nature of what is being transported, unlike cargo, freight, or load. Assets are useful or valuable and resources are things we draw on in order to function effectively. Even when our informational objects are at rest we call them files, which are objects intended to be ordered for easy reference and retrieval. With information technology, was there no tree before there was lumber?

Ideology at the Birth of Soylent. In a blog post from 2013 (available only via the Web Archive) Rob Rinehart, co-founder and early-stage CEO of Soylent, begins by saying that “Food is the fossil fuel of human energy.” Although later on he acknowledges in his section on “Social Implications” that “Food can be art, comfort, science, celebration, romance, or a reason to meet with friends,” the thrust of the vision is clear: food is now a natural resource with a standing-reserve of nutrients, ordered, on-call, ready to be put to work as fuel for the body with maximum efficiency. Rinehart plays with the idea of technologizing dating in a similar way in a blog post later that year.

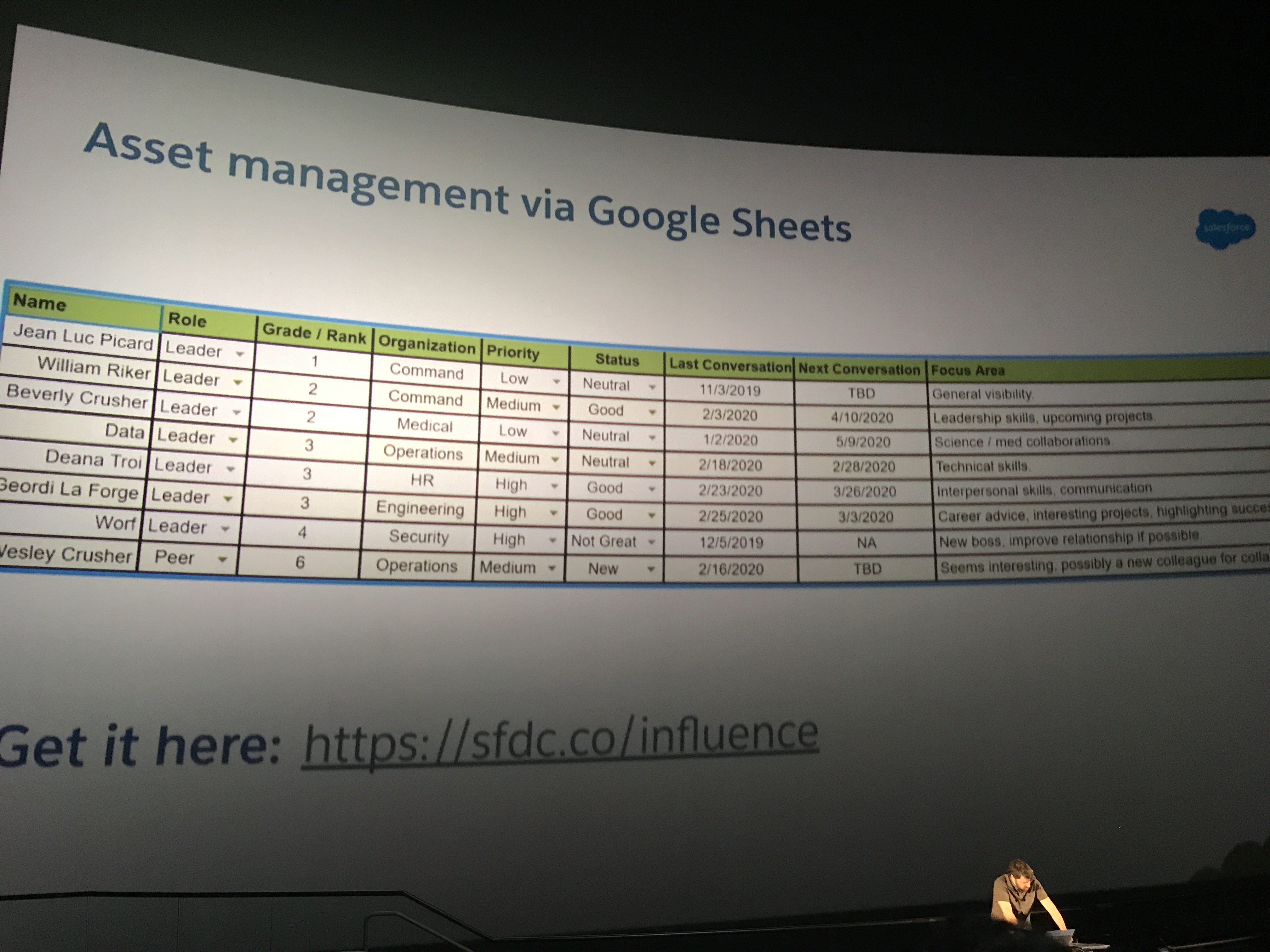

Financial Portfolios, Asset Management, and People. Porter Gale published a book in 2013 called “Your Network is your Net Worth.” The phrase has become popular. She takes language from portfolio management and applies it to human relationships: “social capital… not your financial capital, is the most important asset in your portfolio.” Gale is careful to define social capital as “your ability to build a network of authentic personal and professional relationships.” That is, humans are not to be understood as assets. That nuanced distinction has not always been preserved by others, however. A talk at BSidesSF 2020, a computer security conference in San Francisco popular with tech startups, made the leap Gale wouldn’t and showed how to put humans directly into an asset management list as a tool to get us promoted more quickly. In other words, Google Sheets transforms humans into assets.

Headcount, Butts in Seats, and Human Resources. We collaborate with human resources to manage our teams. We estimate headcount in spreadsheets and work with talent to meet quarterly hiring goals, which is often referred to as “getting butts in seats.” Outreach campaigns for hiring are to be understood as funnels and numbers games where the ideal we strive for is scientific predictability and repeatability at scale.

The Nuts and Bolts of Product and Growth Work. Humans become users or customers. You can buy users with ads. We segment prospects and customers into personas so that we may obsess about how they think, behave, and interact with each other. We seek to know who they trust, where they find their information, and what they value. We question how they may be converted, activated, or retained and engineer our platforms for maximal engagement and business value. We might know them as Dashers, Drivers, Hosts, Pinners, or Redditors.

Heidegger’s Danger & Two Challenges

The lenses of technology seem prevalent in the modern technology industry. Maybe this is the distinct flavor of our water. And if that’s not surprising it is nonetheless revealing in light of the lens view of technology, which we are not usually taught. Our early informational objects were named according to the lenses of technology. As the influence of the technology industry grows so, it seems, does the tendency to view more and more elements of the world as resources. Humans need not be exempt from that gaze.

Heidegger thinks we are headed into dangerous territory. It is irresistible to wear the lenses of technology, he claims. To wear the lenses threatens being totalizing which means that we may not even notice anymore that we are wearing them. If this happens the “truth” recedes. The world is revealed in only one way. Heidegger calls this, dramatically, the danger.

I see two challenges in tech startups today. When we wear the lenses of technology it becomes easy to miss the individual radiance of humans on the other side of our processes, abstractions, technologies, teams, and products. With the lenses on we also become fixed on a singular perspective about what informational objects can be, which limits possibilities and questioning. A JSON is a JSON: a sequence of bytes and a data-interchange format. Why look further?

The Utility of Digging Deeper

What did we gain by digging deeper into technology?

If we accept the Heideggerian essence of technology we see our lives in the technology industry in a new light. We see nuance where before we saw simple truths or maybe nothing at all. We gain suspicion of what initially seems self-evident: that technology is morally or politically neutral, for example. We see new possibilities for further theorizing or questioning the hidden forces at play when we sit at our workstations. It can also be emancipatory because we identified a hidden force. Knowing what’s hidden helps us orient ourselves more freely to the world. Maybe we are now curious about Heidegger’s thoughts on how we can overcome the “danger” of technology. If we aspire to live with awareness and intention then to dig deeper into technology via Heidegger has already been useful.

This isn’t a write-off of the current state of tech startups or technology in general. If we commit ourselves to operating in the technology industry, as I think many of us should, we should also care about how we can do our job better. Have we reached anything useful for increasing our output or meeting our objectives at work? I see three possibilities.

Distinctive Company Values and Culture

The founders of an early stage company are commonly advised to spend 50% or more of their collective time hiring. Oftentimes, founders will doubt their ability to hire the best people they know. The response would be: then you have a much bigger problem. If you cannot convince the people you want that your startup is the best possible opportunity, then you should go find something else to do.

Here a genuine perspective into the lens view of technology or other informed perspectives may become another tool in the toolkit. Such angles on technology can set us apart and convince us of our own ventures.

We might say as Heideggerians: we are not naive. We are here to build a successful business, an awesome technology product, and maybe, if we succeed, something bigger like a movement or a shift in the industry. We understand each other as a team, not as a family. We also acknowledge the dangers of the path we’ll have to travel and are committed to confronting them. We aspire to wear the lenses of technology with autonomy and in accordance with our values. We know when they are appropriate and when they are not. We can dare to do so because we are starting anew, without the baggage of established players, and because we are smart and capable.

To be distinctive, bold, and genuine will help attract culturally-aligned individuals. If the requisite skills are also present, we’ll build strong teams.

Fresh Creative Direction

What might we make of our informational objects if we didn’t wear the lenses of technology? Maybe we could find new ways to interact with them to better engage the spirit of the times, as Harmony Korine’s EDGLRD or MSCHF appear to be doing (maybe the spirit of the times is to AVD VWLS?). Or we might put in our ads that “Software should be beautiful,” as Notion did in several prominent San Francisco billboards in 2024 and 2025.

At Lumos we adopted a company value called “Paint in Pink” with an aspiration to bring new life into the dated, blue-tinted, efficiency-oriented, corporate messaging of the traditional IT industry. Could our tools not only technologize the world, but make it delightful, or feel closer to art? Our collaboration with Krazam embodied that value by aspiring to create content that is genuinely hilarious to IT practitioners, including us.

Motivation, Resilience, and Purpose

The pursuit of wealth, power, status, or belonging can be deeply motivating. Held tightly and confidently, those and similar ends can keep us resilient in the face of ups and downs in the technology industry.

But what if we cannot motivate ourselves with these ends? What if we tell ourselves that they cannot feel purposeful enough? To fill a gap in purpose can keep more of us resilient and present, especially when material needs have been met. And surely we’d want people with alternative goals onboard as we build the future.

Here, digging deeper into technology offers solutions. A deeper look into technology creates space for the kind of reframing and reevaluation that makes fresh kinds of purposes possible.

Heidegger’s perspective on technology, for example, encourages us to see that our collective project in the tech industry is more than business, community, past-time, or political agenda. Introducing new information technology, no matter what our position might be in the effort, is to participate in something foundationally transformative. Not only are we transforming our personal & national economies but our own subjectivities and that of people far away from the whirlwind of action. And yet it is well known that we have not been good predictors of the consequences of new technologies.

So then here is an informed purpose: how might we realize a harmonious relationship (objective & subjective) between the human and the technical in the face of deep uncertainty and massively accelerating technological change?

Thanks to Evan Dorsky, Andrea Lim, and Kelly Wagman for comments.

Martin Heidegger is controversial not only for the specifics of his views but for his associations with the Nazi party and the writing of anti-semitic texts. I agree with others (e.g. see Coecklebergh Ch 3.1) who say we may be justified in being suspicious and critical of his work but not of ignoring it. ↩︎